mimicry (2010) __

the shaman (2009) __

sieg und niederlage (2008-10) __

expansion der gegenwart (2009) __

brigade joussance (2004) __

spaßkulturen (1997) __

international fuel crisis (2007-2010) __

kunst des nationalismus (2006) __

unkirche (2007) __

widerlegung der unterhaltung (1998) __

traktat über die schlange (1998) __

turns (2001-2009)

___

mimicry (2010) __

the shaman (2009) __

sieg und niederlage (2008-10) __

expansion der gegenwart (2009) __

brigade joussance (2004) __

spaßkulturen (1997) __

international fuel crisis (2007-2010) __

kunst des nationalismus (2006) __

unkirche (2007) __

widerlegung der unterhaltung (1998) __

traktat über die schlange (1998) __

turns (2001-2009)

“The worst readers are those who proceed like plundering soldiers: they pick up a few things they can use, soil and confuse the rest, and blaspheme the whole.”

Friedrich Nietzsche, Mixed Opinions and Maxims, 1879

“All men by nature desire to know. An indication of this is the delight we take in our senses; for even apart from their usefulness they are loved by themselves; and above all others the sense of sight. For not only with a view to action, but even when we are not going to do anything, we prefer seeing (one might say) to everything else. The reason is that this, most of all these senses, makes us know and brings to light many differences between things.”

Aristotle, Metaphysics Book 1

1) Anthologies and the birth of style

aAnthologies (gr. anthos: flower; legein: to gather) were originally compilations of texts presented in a book. They provide a survey of a field of scholar interest, e.g. a jazz piano anthology.

bA compilation does not provide a statement per se as it only collects different points of view on the same subject. Yet, an implied statement is that there are different statements at all, a diversity or historical necessity that influence the individual conscienceness, the writer, enabling him to synthesize new information from this ‘compiled’ point of view.

cThe procedure of ‘anthologising’ resembles the work of DJs, the main characteristics here being the confidence in the choice of style.

dOne can distinguish between vertical and horizontal anthologies:

1) A “vertical anthology” provides historical consciousness, that is, an awareness of types and styles: to have style means to distinguish between what is ‘in’, what was ‘in’ and what will be ‘in’ (and the same with ‘out’). For instance, an appropriate collection of films or LPs helps one understand what is meant by “the Fifties” or “the Seventies”. Remakes of movies, retro movements in the fashion world and cover versions in Pop music represent a vertical orientation. Here, the all-over question is: at what time in history has there been what kinds of aesthetic preferences?

2) A “horizontal anthology” gives a simultaneous overview of those styles which a contemporary culture inheres. It also creates style awareness by spatial cognition: in what media and what places do we find specific preferences? Let’s say a famous fashion designer travels around Europe to learn of new collections, new ideas that may influence his own creation. He/She gains awareness of contemporary moods, attitudes, behaviors. Another example are Paul Klee’s and August Macke’s travels to Tunisia. Or: artists visiting dozens of exhibitions in New York in order to create a context to his/her personal work and particularly to position one’s own saying and doing.

eIn this text I like to think of anthologies as principles or methods of perception. Therefore, a distinction between vertical and horizontal anthologies reflects on the possibility of cultural examination. Both are simply anthropological models that help to explain contemporary phenomena.

fI argue that as soon as anthologies emerge the consciousness about styles emerges. This means: a style is not an entity per se. It defines itself either by historical comparison or by distinction within society (Bourdieu 1979). Everybody in the field of cultural production is aware of this fact. The artist’s main source is the instinct for distinction.

gThe Millennium debate was a unique opportunity to ‘anthologize’ historical facts. The exhibition in the Whitney Museum, which was called ‘The American Century’, was simply an anthology of art, its implication being that all single approaches and works can be subsumed under one headline. How is this possible?

Every artwork, every philosophy gives a definitive statement or at least a definitive question about its position in the world. This is what makes it memorable, important, striking, powerful, etc. The question of style does not appear at first. At last, when one realizes that there are infinite numbers of definitive statements or questions we coin the term ‘style’ for the particular approach. Consequently, the artwork in the Whitney show is divided into sections, chronologically but also thematically. Again: This is not at all self-evident. The pieces could have been related to each other considering inherent ideas by analogy (I do not mean ‘thematically’); or: considering the places where they have been shown originally; or: considering analogies in ordinary life and movies; or: considering the artist’s persona; or: considering what artwork looks like art and what does not; or... All this is ‘American Century’ as well, if you want.

hFurther, New York itself can be considered an anthology, the orientation being horizontal rather than vertical. “I am not interested in the past.” says, for instance, Jerry SALTZ, an art critic of the Village Voice. Or New York ‘seems’ to be horizontal and it ‘looks’ and ‘behaves’ vertical.

iHorizontality in the art world always means awareness of the market, of trends and of competition. No one here is diving deep into the ontologies of works of art. The idea that art matters socially or metaphysically is far away or seems just a particular strategy of the market. My own assumption is that it never has been really different and that metaphysical and moralistic imperatives, what art ought to be, stem from typical bourgeois circles, that is from that part of society which is considered by artists usually as the dead end of cultural/critical awareness.

j ‘The real art was never real?’ is the question. ‘No’ say all the disillusioned artists. ‘Yes’ say the decadent artists and the bourgeoisie. They say ‘art matters’, because they know that matter ‘matters’.

kIt is important to stress that the vertical and horizontal properties a culture inheres are interwoven in the ‘real’ world. The ‘living world’ (Lebenswelt) has no ‘real’ form. Every culture creates its own forms by distinction. It does so in order to cognize. The Whitney show, curated by an Australian tribe, would have provoked other questions than the actual exhibition did.

lDistinction is a method of interpretation.

(1998)

2) Transitional Ontologies

aAccording to the hypothesis of transitional ontologies perceptions of events, things, facts or moods define their own frameworks of evaluation. Those distinguished frameworks or ‘worlds’ are not coherent or ‘compatible’ but each of them inheres a common subject/object relation.

bIn other words: every time a person is certain about a fact the certainty is based on a background of experiences which are unique in relation to this certainty. Each certainty is based on a different ‘framework’. One person’s certainty about the existence of God is distinct from his/her certainty that the sky is blue or that another person is lying or that a stone falls to the ground.

cThere are no criteria to find a common ground for all certainties besides the fact that we all are ‘in’ language. While Newton’s law of gravitation seems to explain our conviction about the falling stone, no law in physics is able to explain the belief in God or personal intrigues.

dImagine rivers in a natural landscape to represent our convictions. Then their origins stand for the cause of being (their particular ontology), and all environment which causes the origins stands for experience.

eDuring the Medieval Ages people believed in just one origin which leads to the main river.

fAn empiricist like LOCKE would not emphasize rivers but rather the environment. For him the term origin does not mean ‘source’.

gPLATO would think of a landscape design or he would look for caves and think on the sunlight.

hA ‘postmodern’ thinker would claim that there is no connection between river and origin.

iTransitional ontologies states that every river has its own particular origin and that the paths a river takes change with time.

jArtists are those people who fish in the rivers.

kThe river allegory contains some other implications, like the notion of the ocean, which you, the reader, are encouraged to inquire.

3) ‘Knowledge-ness’

aComing to terms with ‘being in the world’ is an artistic task. Traditional metaphysics since Aristotle up until Heidegger deals with ‘being’ as an entity either founded on a transcendental ego (Descartes) or on a transcendental world (Heidegger).

bThe French rationalist gained certainty of the ego by doubting all that exists realizing that he cannot doubt his doubt. The conclusion: “Dubito ergo cogito. Cogito ergo sum.” Existence, according to Descartes, is therefore the critical awareness of oneself independent of a real world ‘outside’.

cIn the contrary ‘being-in-the-world’, as Heidegger puts it, constitutes the individual notion of ‘being-there’ (personal existence). This means the personal ego is a residue of a network of other existences; and each other existence is a result of the contact with others as well. Considering Descartes’ model this means that personal doubt cannot be regarded as personal in order to gain certainty about oneself and the world.

dFor instance, everyone was once told that the shiny piece of metal which we use for eating is called ‘spoon’. ‘Spoon’ relates originally to a specific person, probably mother or father, who mentioned and explained the use of the word to you for the first time. So does the notion of ‘I’. ‘I’ relates to and was explained by ‘you’, ‘him’, ‘her’, ‘them’. ‘I’ is not an invention by ‘me’. The idea that I am is not my idea. It is Descartes’ idea that “cogito, ergo sum” but by saying this he paradoxically cannot mean himself. ‘Being’ relates to the plurality of others.

eThe purpose of this text is to describe how it is very difficult to find the Cartesian point of certainty particularly in New York. My claim to begin with: The appropriate philosopher for New York is not Descartes, it is probably Martin Heidegger.

This means: if we search with the Cartesian method we will come to the conclusion that there is an infinite number of possible approaches on certainty, on values, etc. which refers to the notion of postmodern paradigm. Hence, if we do not consider doubting but rather interpreting the given possibilities for life (Lebenswelt) our conclusion is that the Cartesian point is unnecessary to look for as we are already within it.

f Some statements in the art world imply that stylistically anything is possible simultaneously because divergent aesthetic schemes of preference exist. Postmodern uncertainty resembles Descartes’ state of doubt. Postmodern thinkers believe that there is no end, no conclusion of this doubt. My assumption is, however, that the difficulty to ‘experience’ our culture in time (through history) causes ‘asymmetrical’ interpretations of our present.

gConsequently, I have found the ‘postmodern’ interpretation of Western culture always asymmetrical. One reason is the claim of the uniqueness of our historical condition, another is the escape into ironic positions and self reflections (painting about painting; the fake is more ‘real’ than the original; media virtuality describes reality; every position finds it anti-position; every sincerity is strategy; every belief is knowledge, etc.).

hThe state of being that is described by postmodernism is a state of permanent knowledge of oneself accompanied by a skeptical attitude of not-knowing oneself.

iIf ‘being’ means ‘knowing’ the state of ‘knowledge-ness’ can never be surpassed. And further, the wish to know more about oneself led to the nihilization of oneself.

4) Philosophical zooming & the demise of the ego

aThe destruction of the ‘ego’ began slowly in the 19th century and intensified in the beginning of the 20th century. I will pick out some of the major statements to underline this fact:

bTo start with HUME: in the 18th century the empiricist considered the self as “nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and movement.” (A Treatise of Human Nature I, IV, § VI)

cNIETZSCHE refers to conscienceness as a mere product of evolution. In “The Gay Science” he proposes that awareness of oneself emerged as a biological need for distinction within social groups of early humans. Furthermore, he criticizes Descartes’ ‘cogito’ because of its inherent problematic.

“Where does the concept ‘thinking’ derive from? Why do I believe in cause and effect? What gives me the right to speak of an ‘I’ and even of an ‘I’ as cause, and finally of an ‘I’ as cause of thought? ...

... When I analyze the process that is suggested by the sentence ‘I think’, I find a series of risky assertions whose basis is difficult, perhaps impossible, to establish — for instance that it is ‘I’ that am thinking, at least that there must be an activity and a function of a being which can be considered to be taking an initiation that ‘I’ exists, and finally that what ‘thinking’ means has already been established, that I ‘know’ what thinking is.

...It is falsifying the facts to say that the subject ‘I’ is a condition of the predicate ‘think’.

A thought comes when ‘it’ wants, not when ‘I’ want ...

‘It’ thinks but that this ‘it’ is identical with the good old ‘I’ is at best only an assumption.”

(Beyond Good and Evil, § § 16-18)

dWITTGENSTEIN diminished our authority on our own thoughts by examining the use of words and refusing the idea of a “private language”. Regarding to him nobody can be certain about one’s own thoughts. Those are only eminent when expressed by language which itself is a social convention. Further, the use of the word ‘I’ is conflicted with senseless notions of a bodiless spirit.

“we don’t use (‘I’) because we recognize a particular person by his bodily characteristics; and this creates the illusion that we use this word to refer to something bodiless, which, however, has its seat in our body. In fact this seems to be the real ego, the one of which it was said, ‘Cogito, ergo sum’.”

“‘I know what I want, wish, believe, feel ...’ ...is either philosophers’ nonsense, or at any rate not a judgement a priori.”

“I can know what someone else is thinking, not what I am thinking. It is correct to say ‘I know what you are thinking’, and wrong to say ‘I know what I am thinking’. (A whole cloud of philosophy condensed into a drop of grammar.)”

eFREUD split the entity of the individual into a trinity of ‘Ego’, ‘Id’, and ‘Super-Ego’. Stating this he makes us all patients of his, somehow, because all these spheres are in conflict with each other. The individual seems just a predetermined result of drives that appear in childhood and that explain actions and behavior in adulthood.

fLEVY-STRAUSS in a statement about identity emphasises the lack of psychological entities whatsoever:

“I never had, and still do not have the perception of feeling my personal identity. I appear to myself as the place where something is going on, but there is no ‘I’, no ‘me’. Each of us is a kind of crossroads where things happen. The crossroads is purely passive; something happens there. A different thing, equally valid, happens elsewhere. There is no choice, it is just a matter of chance.” (1977)

gBiologists MATURANA and VARELA disillusioned the notion of integrated organisms by applying their systems approach to the living world. Systems thinking gives up the idea of an idealistic ego replacing it with a network organization. Accordingly, modern neuroscience speaks of the “dance of neurons” when referring to the ‘self’. Richard DAWKINS ‘accuses’ our genes of taking the leadership in the evolvement of organisms.

hMost contemporary authors deal with the ego either as an author or non-author (BARTHES, RICOER, LYOTARD), as a social being (LUHMANN, GIRARD, BOURDIEU, LATOUR) or as an existential agent in the world of media (FLUSSER, BAUDRILLARD).

The tendencies are: either the ego as an ‘author’ vanishes, being purely a matter of text; or the social being disappears in systemic collectives; or the subject is considered a mere result of media communication.

iFinally, there exists an attitude in contemporary American philosophy to diminish the role of an ego to a mere ‘narrative’, as a cross-over of texts, stories, expressions. Particularly Richard RORTY is a participant in recent ‘deconstructivist’ efforts.

jLet us resume: in the late 20th century we find no assertion of an aprioric structure, entity or impression which we used to know as ‘I’ in the theoretical discourse.

kOne analogy is the scientific enquiry of atoms. First, an atom seemed an entity. Later, research proved that it consists of electrons, neutrons and protons. Nowadays, sub-structures like ‘Quarks’ or multidimensional ‘Strings’ are proposed. Modern physics describes fields which are based on probability rather than particles which are based on trajectories (= determined paths in space-time). Atoms are not relevant anymore in the way there used to be.

l That is to say, it would be wrong to state that atoms do not exist. They do. But today they are embedded in a more diverse field of theoretical hierarchies than a couple of decades earlier. And this ‘effect’ applies to the notion of ‘I’ in the same manner. The ego has not disappeared it only has become an element in a wide field of psychological mechanisms. It is not the main element anymore.

lImagine a philosophical (not a physical) camera zoom towards a person. As soon as we encounter the person the image changes into a substructure: we do not see the individual anymore: instead we see stories, relatives, etc. When we zoom further into a relative of the person the image changes again. We see other stories, persons but also aspects of our initial person. We see him/her in the way s/he is perceived e.g. by her mother. We zoom into the person again. This time the image is slightly different. What we see of a person is always changing; and what we don’t see remains the same.

(1999)

5) The gap

aAs one result of analysis we are able to create an anthology (a “bundle” how HUME stated) of statements, of narratives; a crossing point of narratives which constitute a vague idea or resemblance of former notions of the self (R.RORTY 1991).

bOn one hand, this notion can be represented as an anthology of ontologies.

cOn the other hand, there is an empirical ‘I’ which is called by name. Despite a theoretical nihilation of the ego everyday life gives proof of the opposite. It appears that the contemporary world ‘I’ enhances notions of individualism. At least this tendency is noticeable in I-centered advertising strategies since the 1980s – in the sense of “Be yourself”. Yet, who or what is addressed here?

dThere is a gap between the ideal part of life and its pragmatic real part. Yet, we know intuitively that we need both parts to live. Is this the state of “unhappy consciousness” (unglueckliches Bewusstsein) that HEGEL examines – the consciousness that is torn apart between the world and the self?

6) ‘Being is being perceived’

aTraditional ontology, as Aristotle puts it, is an investigation in the nature of the being of all that is. As this investigation must be a part of its subject (all that is) it’s method is to perceive the way things are in the way they are.

bAnalogies of this concept can be found in diverse fields of cultural and scientific studies. 1) Well known are epistemological problems in quantum theory. Particularly apparent is the impact an observer has on the subject of his investigation. 2) Another analogy are espionage movies where an observing agent happens to fall deeply in love with the observed spy thus corrupting his investigation.

cIn both cases - necessity (1) and love (2) - the result of the observation is definitively ‘subjected’. We do not gain the ‘pure’ result because I cannot distinguish myself from the result, and I cannot distinguish the object from my investigation.

dRelating to this issue, biologist Humberto MATURANA proposed the distinction between transcendental and constitutional ontologies. By latter he is referring to the function of experience to construct an image of the world. An explanation with no necessary observer involved, according to Maturana, is transcendental.

“Obviously, correct propositions in certain areas of reality can be false in other areas: ‘Here’ they are valid but not ‘there’ (...)

This insight stems from the path of the ‘objectivity in quotation marks’ and it is the basic condition for understanding the observer/ the observation. Who reasons about ‘cognition’ without considering an observer places his thoughts into the realm of the ‘objectivity without quotation marks’. Here, all questions about ‘what exists’ are answered with things ‘in itself’ which are independent of an observer in order to justify the given solution. These explanations I call ‘transcendental ontologies’ (...)

The other realm I call ‘the domain of constitutional ontologies’ where the proposition and image of an object are ‘constituted’ by observation.” (Humberto MATURANA, “What is cognition?”, 1994 – Transl.ZT)

eAt this point, I would like to switch to the art context. Ontological considerations are inherent in the relation an author/artist has to his work. Some historical examples I think of:

1) The Minimalists’ claim of an ‘out-of-the-world’ presence of their objects idealizes perception by ‘extinguishing’ both artist and audience. Here, being is not being perceived; being is ‘expressed’ by form. These forms are thought of to ‘stand out’ from the real world. They ek-sist, so to speak, imposing a genuine difference between object and phenomenological horizon of objects.

Toni SMITH expresses this attitude by saying that

“I am not aware of how light and shadow fall on my pieces. I’m just aware of basic form. I’m interested in the thing, not in the effects — pyramids are only geometry, not an effect.” (1966)

2) Photorealists like Chuck CLOSE seem to ‘express’ that the artist’s hands should not be the primary aspect in the imagery by painstakingly rendering a photograph. The authority of the photo seems to dominate the painting and thus referring us to the medium. Yet, the opposite is the case: it is all hands we see when we realize that it is a painting and not a photograph. By this we are referred to ourselves because the doubt about the nature of the artwork baffles us, makes us find a position towards it. It is a state of delight when you cannot believe your eyes although it is not delightful to admit this.

3) Robert IRWIN’s installations inquire the being of a perception rather than any other ‘being’. He defines the experience of seeing by stating that

“Seeing is forgetting the name of what you see”

Again a change of consciousness is proposed in the presence of art. The ‘look’ of the object swallows ones awareness. IRWIN’s statement resembles a theme by Jean Paul SARTRE where, how the French existentialist elaborates, we ‘vanish’ in the awareness of looking into the eyes of ‘the other’. And it has a BERGSONian touch: either we look into one’s eyes and see the person or we notice the color of the eyes and we do not really see the other.

One can follow these three examples and ‘observe’ how the role of the observer appears. 1) is pure metaphysics at first sight, but the delight of this approach derives from the impossibility of omitting the eyes of the beholder. 3) is the opposite: it appears to omit the object. 2) is an intermediate position leaving the observer in a both passive and constructive position.

f In the question of being is necessarily the question of an observer involved. This notion relates to the social world as well as to the scientific world. And it relates to the synthesis of the social and the scientific: the art.

7) Too good to be art?

aCultural creations depend on individual pursuit (“will to form” A. Riedl) and its correlative artifact (painting, writing, etc.). If successful a creation transcends its subjectivity and gains socio-political relevance by ‘making sense’ to others. No matter how idiosyncratic a painter works: if only one person finds it beautiful it means that the very same ‘world’ that was ‘in’ the artist was or is now in someone else. (Either there is only one world and it can be read in plenty ways or there are an indefinite number of worlds but there is only one reading.)

bHere, art becomes the bridge to ‘the other’. But ‘the other’ is already in the art work because s/he is already in the artist. The artist represents the audience as well as himself while working. In our context art is a reassurance of the fact that one is not alone.

cThis aspect gains importance in the world we call New York as the social relationships indicate the level of being-there.

dWhen one resumes empirically what kind of art works are being liked by whom one could come up a ‘social law’ of perception. One likes in other art what one does with his own artwork. Yet, there are happy little moments when one piece transcends this law and is appreciated by a majority. In these moments the art work becomes ‘good’ in an ancient Greek sense. The term agathon means ‘good’, ‘beneficiary’, but it is used together with kalos, ‘beautiful’. The Socratic kaloagathon is the identity of the good and the beautiful. This is what we mean, nowadays, when we say about an artwork “This is great!”. It connects simply to a plurality of positive notions that are socially relevant.

The contemporary use of the term ‘beautiful’ is reduced to the notion of ‘pretty’.

eI remember situations where I was not able to comment at all when being confronted with certain types of work of art. If this happens something is missing that would lead me to the experience of the ‘good’. Even if a lack of competence lied on my side, ‘good’ art nevertheless would be able to speak to the incompetent as well.

fArt that attracts the most people is successful art, is good art, is high art. Art that does not attract masses has at least one problem. Either it is too good, or it is too bad.

8) The ‘fashion of art’

aI like to remind you of the distinction between vertical and horizontal anthropologies (chapter 1). The terms ‘vertical’ and ‘horizontal’ derrives from contemporary anthropology (e.g. Latour 1989). Horizontal information relates to spatial aspects in a contemporary culture whereas ‘vertical’ emphasizes the historical nexus (intergenerational sharing of information).

bVertical anthologies are usually associated with works of art, fashion is more horizontal. This is the historical burden of art practice that permanently challenges, dismisses or ‘improves’ the status quo, but by doing so provides the framework for paradigm shifts that usually are interpreted as stylistic periods. Horizontal anthologies relate to mere “fashion effects” that are not sustainable and do not survive a decade or so (‘the 1950s’).

cThe notion of a style in Western art usually means much more and has more ‘depth’ than the notion of style in the fashion world. Art style is super-temporal (“ueberzeitlich”) while fashion styles mean the opposite: being within the framework of contemporary issues (The German term ‘Zeitgeist’ which comes from Hegel expresses what is meant by “within the framework”. It means literally ‘time-spirit’, that is the specific aura or character of a particular period of time. On the other hand “super-temporal” states that people and artifacts are not defined by their time but rather define time and also are capable of voluntary change by free will which is called ‘creation’).

dOne hypothesis of this text is the rejection of the superficial differentiation between art and fashion without turning art into a fashion skirt and fashion into a monument. Art seems high, fashion seems low. But “high and low” does not necessarily mean good and bad. ‘High and ‘low’ are just dots on a cultural map, not the route we are to follow.

eYet, this indifference may become problematic when one sees artists posing like fashion models in front of her work for the VOGUE magazine (Damian LOEB, Cecily BROWN, 1999). The self-confidence of the presentation and the claim that e.g. Mondrian has done the same by placing his paintings in a fashion magazine in the end of the 1940s are not satisfying because art & artist are displayed passively rather than taking control over their presentation (e.g. being in charge of the lay out or the shooting etc.) and thus making their presentation a part of their work.

fThis is what we artists of the future will have to deal with: the self-confidence of new categories.

gAnd this will possibly provoke the ‘other’ kind of art.

9) “What is obvious?”

aIt is becoming personal now. In 1999, I just finished my first year in the art college, Richard TUTTLE came into my studio. The two things I remember were:

1) He talked about that there has been a discussion in theory whether an artwork should have an idea or whether it should not. Recently, according to TUTTLE, one has come to the conclusion that works of art should have an idea.

2) He looked around and asked me: “Where is the art?” – I had no idea.

bThere were some paintings, some objects displayed in my space. Anyhow, I started to think about what he said, and I realized: yes, indeed, where is the art?

cAfter he left I started an inquiry but I could not find any art in my studio. TUTTLE was right.

dBut what I learnt from this encounter was: he was wrong as well because if you look for art you will never find it. If you expect art it will never hit you. And when you are stepping in a student’s studio to give a critique, you expect art.

eMe thinks, people who expect things that they understand are called experts. Hence, it is easy to surprise them.

fHowever, what can you expect from a non-expert?

gSome things are obvious. But the obvious is not easy to see and it is blurred by experience.

hIt is obvious that we look up when we point to the skies. We do not look down. Someone has to state the obvious to make it obvious: someone may claim that what we call sky begins already 1 mm above the ground (the border of the sky is the earth’s ground on one side and the vacuum of outer space on the other side). Now it is obvious.

jIn this regard art has the obligation to state the obvious. By stating it, art defines what is ‘there’ and what is ‘not there’. What is ‘there’ is subjectively and objectively ‘there’. What is ‘not there’ is either not there at all, or it is just objectively ‘there’.

kBack to my studio and Mr.TUTTLE: perhaps the art was not missing but rather a definition of what actually was ‘there’ and what was not.

lAn artist does not make art. He or she defines what being-there means, defining the obvious and stating the improbable.

10) The sparkling moment

aA colleague of mine, Daragh Reeves, once showed a ‘Coke sculpture’ in his studio. It consisted of several small glass containers completely filled with Coca Cola so that they looked like solid brown tubes. During a group critique Reeves emphasized his notion of the piece as a sparkling phenomenon. He emphasised how the bubbles animate the drink and thus the sculpture.

bAfter a while the sparkling effect disappears, naturally. For some critics this seemed an unsolved problem. He was asked: “The sparkling effect, how do you want to show that?” was the question.

cI do not remember the actual answer, but the correct answer would have been: if you are reluctant to see what is there in front of you nothing can be revealed to you.

dThere is so much of an attitude apparent in such a simple question. It says actually:

“How do you want to show that, what I just saw with my own eyes but what I refused to accept at the moment I saw it as the ‘real moment’? How do you want to show it later what you just showed to me, once the effect has disappeared?”

eNot accepting the moment means to think in ‘museum style’: a thing exists only when it is or can be preserved for future generations. A customer of a Deli-philosopher would say ‘to stay, not to go’ (see chapter below).

fStudent for life! The important thing is here and now in front of your eyes. When perceiving do not position it in an imaginary art-space where it could be seen as ‘real’. Because it is already in an imaginary art-space. It is already what it is — now.

gDuring my two years in New York I noticed the inability of a lot of artists to think in and with the moment. With latter I mean an ability to see the uniqueness of a creation without considering the consequences of its being-there.

hIt is true: you have got to earn your questions. If you do not deserve it nobody will ask you anything of particular importance. I remember our lecture series at the School of Visual Arts (1998-2001). Some of invited well known artists thought their mere presence did the job. It did not. Fame is not enough to prove that you are a good artist. Surprisingly, they did not understand that they only could have show their art if they had presented it performatively ‘here and now’ – in any form – during their presentation. Instead – what has established itself as a common practice – some artists mimic the gestures of curators or art historians. They are ‘doing’ or impersonating an artist instead of being one.

iIt is essential to understand the moment in art. What it means. Because art happens, if it happens, – the sparkling moment, I mean – when you are the loneliest creature in the universe, and the relevance of art practice is revealed when you are interacting with others. These are the two aspects of the sparkling moment.

jI noticed during the entire lecture series at SVA that sometimes to show something seemed to be the reason to speak, and sometimes the words are the reason to show something. Ideally, there should be no reason involved.

kStudent for life! Understand and stand the moment! And do not forget the sparkling!

l Because, in fact, there is nothing else than sparkling.

11) Art that looks like art : prop painting

aImagine you want to make a movie. For the scene in a living room you need art work which is instantly recognizable as such by the audience. Of course, it will be a painting. Remember: the focus is on the main characters in the foreground, which means that you have to look at the painting with the ‘white of your eyes’. At the same time you should be fully conscious of it as a piece of art. Props are not supposed to be dominant but they are supposed to be fully present without being dominant. If they were not present a disturbance would occur that would distract from the main characters.

bThe task that a painting should be recognizable as what it is sounds easier than it really sounds. Richard TUTTLE refers to the identity of an artwork when he states:

“It is however an estimable fact that an artwork exists in its own reality, and in that exists a certain cause and effect pattern which has baffled the ancients as well as myself. To make something which looks like itself is, therefore, the problem, the solution.”

“To make something which is its own unraveling, its own justification, is something like the dream. There is no paradox, for that is only a separation from reality. We have no mind, only its dream of being, a dream of substance, when there is none. Work is justification for the excuse.” (1972, Documenta 5)

cWork is justification for the excuse. This is the prop for this essay. Analogous: The painting being present for the sake of a movie.

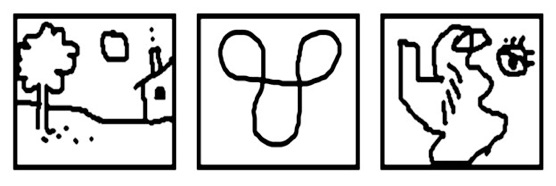

dLet us further consider how a prop-painting may look like. I remember that in many comic strips that I have read in my childhood paintings that appeared in, let us say, an office background looked just about like this:

A B C

If my memory serves me right the most common representations point to a modernist paradigm about the ‘looks’ of art works. It is either representative old fashioned (A) or ‘abstract’ modern (B, C).

eFurthermore, it is somehow ‘out there’ (art, aura, not life), but it is ‘in’ as well (as a piece of furniture, daily life). This constellation seems perfect for a painting that looks like a painting, or like a prop for itself.

fAs a part of the movie background our prop-painting must not have a background in itself. It needs to lack any stardom. It would be wrong to display a copy of a well known Picasso. Instead one would choose a motif that resembles something of it, something that is similar (analogous to fast food: food that does not have a memorable taste but rather looks like food instead of beinf proper food).

g One could say, prop art needs only itself because it is needed by others to be itself.

12) The ‘fish’-problem

aThe artist did it. He projected an image of a dolphin on a little waterfall (in a gallery space in Chelsea, ca. 1999). But — wait a second, there is a mistake. Firstly, we suppose, he had the idea to project an image on a waterfall. OK, good idea, perfectly acceptable. Then, secondly, there is a decision about a particular image, a decision about the what. In his case it is a fish, and it is a failure because it is a final decision, a fixed reference which deteriorates the initial idea.

bThe ‘what’ is already there, namely the ‘what’ of the idea, the setup (projecting x on a waterfall). ‘What is it about’ is not a question. It is about what. The initial idea inheres all possibilities of a content (what Adorno called Gehalt = content).

cYou can project anything on the waterfall. This becomes a problem when you begin to make an object from this idea. You have to show something. You cannot display anything (an eternal judgement in the Kantian sense), you must display something. The artist came up with the idea to actually project an image of a dolphin. His solution is not as unexpected as it ever can seem to be. Something is wrong.

dOne could perhaps generalise this problem in the sense of a biblical commandment. The 11th commandment would say: You shall not show ‘fishes’, that is: the pretension of knowing final solutions for eternal judgements (dialektischer Schein, according to Kant). A piece of art is not like a stuffed turkey; the turkey being the formal idea, the stuffing being the actual content, because the turkey is already ‘content’.

eIf the idea had been to show a tiny waterfall inside of a dolphin the exhibition probably would not have failed. But it appeared as a turkey which had to be stuffed.

fHowever, the failure to see this is acceptable if you accept the failure of your art work or the failure of art in general. The acceptance of complete failure is a genuine aspect of art practice. The worst aspect in above case is that it is an indifferent failure; you cannot distinguish it from a success. The show did well, the artist did well, the whole set up did not miss anything. But – you do miss something fundamentally. And if you miss your need to miss you feel dissatisfied. If you do not notice this you probably will never be dissatisfied. And that is a kitsch kind of existence, being something else for someone else.

13) Deli-philosophy: “To stay or to go?”

aAny philosophy exists because of distinctions, the most famous being Descartes’ res cogitans and res extensae (thought and spatial substance).

bOne possible distinction: I am interested to find big philosophy in small areas, big thoughts in small spaces, like Delis — or you can say: I am interested to find res cogitans in res extensae.

cI think of everybody as a philosopher with a potential to find eternal human truths and values (however problematic and idiotic this may sound – I am excused for now). These truths may reveal themselves in moments that are as trivial as other moments in everyday life. Yet, there is no real triviality in life, and, strictly speaking, there are no moments of truth. But there are observations of triviality and of truth. And we think of them as moments. I suppose, these are our tiny pleasures in life.

dPresocratic philosophy brought about metaphysical concepts of our cosmos that today can be described analogous to conversation bits one ancounters in Manhattan’s Delis when ordering food. They ask you: “To stay or to go?”

eWhat they are really asking – if they had the time to talk about it – is: Do things remain the same (as Parmenides thought) or is everything transitional (as Heraklitus believed)?

fThe Deli-philosophers with their not-so-delicious food point out that the Pizza slice remains the same, whether for to go or not, but the service is different and the taste changes if you wait for too long.

gDelis are transitional places. They are ‘to go’ and not ‘to stay’. In my two years in New York I did not develop a firm relationship to a particular Deli because they all offer mostly the same products. This describes the indifferent part, the ‘to stay’ aspect. The products will be the same wherever and whenever I go to purchase them.

hTake the deli-fruits for example: I distrust the fact that they look so identical in a way that leads me to the conclusion that there is only one source where they are distributed from. Same size, same color, same taste, same ‘design’ – really everywhere. But I know for a fact that tomatoes, apples and bananas can taste different, can taste better.

iA friend who worked for an import company explained how they ‘do’ bananas: When the fruit arrives it is green. Then a little container with liquid gas is placed in the center of the hall where the bananas are stored. When the ventile on the container is opened the worker speeds out the hall to escape the influence of the dissipating gas. After ten or more minutes the gas is expired. The bananas are ripe and equally yellow. They are ready to go.

14) Franchising and Art

aOK, American reader! This I have learnt by now: Behind appearance there is always a method. I am not looking at your soul, I am looking at your hands! And what do I see? Methodology. The reason to do things instead of contemplating them.

bSociologist George RITZER describes in “The McDonaldisation of society” (1989) how ideas of rationalization, efficiency, control and redundancy infiltrated American society. He refers to Max WEBER’s theory of rationalization and tries to inquire, among other phenomena, origins and structure of American franchising ‘behavior’.

cIndividual freedom is an American ideal but it is not efficient for the business. And, individual freedom is solely for individuals. Yet, not everybody is an individual.

dAll employees of McDonalds, for instance, have a strict plan of behavior in order to enable certain standards. The broiling of burgers underlies a strict procedure to make sure that they are cooked equally. Even the conversation between employees and customers is standardized. In some major supermarket chains the employees at the cashier have to smile for at least three seconds to welcome the next customer on line. The appearance has method. So, where is your individual freedom? Even those guys who design such mechanisms are not free, and even the bosses have to look carefully that all procedures are followed. So, who is indicidually free? People behave like machines, and even on vaccation I can imagine them to not being able to turn off.

eA nearby example: the School of Visual Arts. Student employees are told exactly what to say when either the school’s chair or president or another important person calls. Individual behavior is not at all encouraged. The system needs to be efficient. It is not, however.

fIf you are a pessimistic analyst you will discover a fascistic scheme behind these structures: alienation, centralised organisation, pushing ‘inhuman’ or pseudo-human behavior, centralis power structure, bureaucracy, race-based distribution of quality of jobs (African Americans, Indians, Asians, Hispanics etc. in lower income jobs)

gIf you are more optimistic you will stress the positive aspects of rationalization: efficient products, acceleration of developments, trust in brands, etc. Happy fascism. Be a happy fasist.

hNon-individual non-free behavior is an American ideal as well.

iIt frightens and gives delight at once to notice or at least to predict franchising effects in the artworld. Some NY galleries have branches at different locations (GAGOSIAN, ACE). And if one is sensitive one will notice tendencies in works of art to standardize communication. Once someone is convinced by a certain concept (slick abstract paintings for example or Big Macs) he will expect more of that kind. It does not matter by whom, almost.

jI said it frightens and brings delight. It frightens because, on one hand, there is a danger of damaging the role of the artist. On the other hand it brings delight because it offers the opportunity to act properly by simply making art proper.

15) Common sense and strict sense

aFreedom and art. I would like to highlight two holdings of human or artistic nature.

bMICHELANGELO holds that a sculpture is already present in the raw stone. It just needs the hands of a genius to let the art emerge from it.

cJohn LOCKE holds that the human soul is like an empty paper, that it contains nothing until it is ‘filled’ with experience.

cA sculpture done by LOCKE would look like a slick pavement which is a result of thousands of pedestrians’ feet. The slickness is not apriori in the pavement.

dThe English empiricist refuses the claim of innate ideas. We do have the choice to act as free human beings. We are not determined by transcendental principles.

eIn contrary, the sculptor has no choice. He has to reveal what is ‘hidden’ in the stone. He is a tool of the divine spirit which connects him to eternal beauty. Michelangelo is not free to do what he pleases.

fIn German ‘Fine Arts’ translates ‘freie Kunst’ meaning ‘free art’. In common sense this is comprehensible but in ‘strict sense’, as we noticed, not at all. The reason is that common sense and strict sense contain different notions of freedom and necessity. In common sense freedom means approximately ‘important and not necessarily useful but nice’. In strict sense freedom means to create (an action, a tool, a gesture, a sentence, etc.) without necessarily having a choice to do so.

gMy assumption is that opposite terms describe a third ’invisible’ one of which they are a part of. There is a secret unification of all opposites.

hOne example: SPINOZA unified freedom and necessity by claiming that God’s necessity is man’s freedom and God’s freedom is man’s necessity. My interpretation of this statement is that the proof or the necessity of God’s existence is evident in the appearance of human freedom, and reverse. All is in God, as SPINOZA says, and through him and by him. The human soul applies differentiation of terms to cognize, yet, all distinctions are unified in God. This is his freedom. By giving up cognition we are truly free, defined by SPINOZA as God’s necessity.

iThis explains the notion of ‘free art’. It is the artist’s necessity and simultaneously the divine freedom. MICHELANGELO is free in that sense that he accepts to have no choice. By working on his sculpture he falls into the indifference of oppositions. He works from outside, the stone ‘works’ from inside.

jIf we took a divine point of view we would make a strange observation: we looked at MICHELANGELO carving a stone, yet, for us it seemed as if the stone would carve the artist as well. Both are just a simple relation in our divine eyes because we cognize by differentiating between the artist and the object although both are ‘us’. And this is our divine necessity.

kBack to earth. We keep in mind that ‘finishing a piece’ means also ‘getting finished’ by the artwork. Further, we keep in mind that the ‘order’ to do something is a kind of freedom. This is important for some art discussions where freedom has a positive and necessity a negative connotation.

lI remember a statement by John CAGE where he expressed a preference for MOZART because of the openness and freedom of expressions while BACH stood for a strict determinism.

mAfter all, I assume the preference lies rather in the notion of freedom than in the choice between freedom or determinism.

(cab driver, video, 1999)

16) The ownership of ideas

aOnce in a while, when you overview the busy production in art environments like schools you might find similarities between the works. This is due to the well known effect that one learns from fellow students rather than from teachers. One is simply in daily contact with each other, one’s thinking is formed by each other (see chapter 2). It is learning by not being taught.

bStill, there are moments where you claim a certain idea to be your own origin of ‘genius’. In this instance others are not ‘allowed’ to participate in the further development of the approach. “The idea is mine”.

cThe question is: how is it possible that this can be true sometimes and sometimes not?

dI remember a scene from Michael RADFORD’s film ‘Il Postino’ where Massimo Travesi plays a somewhat uneducated character who falls deeply in love with a waitress. He is a postman in a small village on an Italian island and his task is to bring the daily mail to a famous poet who is residing on the island. Well, Massimo becomes friends with the poet who wants to help him composing love letters in order to gain the heart of the beloved lady. Massimo is desperate: being a poet is very difficult. His attempts are, despite of the poet’s help, unsuccessful. So he decides to ‘steal’ some love poems from the author. When latter finds out he confronts him. “How could you use my poems! They are mine!” Massimo replies: “Ah, Signore, poetry does not belong to those who created it but to those who need it.”

eDuring a lecture I asked Ross BLECKNER where his series of mainly black and white fantasy paintings come from. “Where it comes from? I don’t understand the question....I guess, it comes from my brain.” This was not what I asked about. Obviously it seems to be a rather difficult task to inquire the origin of an artwork, that is ‘where it comes from’. I mean, when you see a river you can point to its origin, but when you see an ocean the task is much more difficult. That is, in above case the brain is only one origin, and perhaps the idea of the painting is the origin of the reference to the brain. Who knows? As NIETZSCHE puts it:

“Not that one is the first to see something new, but that one sees as new what is old, long familiar, seen and overlooked by everybody, is what distinguishes truly original minds. The first discoverer is ordinarily that wholly common creature, devoid of spirit and addicted to fantasy — accident.”

Now, this is ‘oceanic’ thinking!

THE END

This text is an edited version of the MFA thesis submitted to the School of Visual Arts, New York. 2000 © Zoran Terzic.